True Story: A few years ago, I was a lone Medical Officer for a health related CSR project in remote rural villages in Gujarat. One day, as usual, more than a hundred patients and their relatives were sitting outside my make-shift clinic, braving the hot sun. All of a sudden, a man stormed in midst of my consult and accused me of taking too much time (I was seeing >20 people in 1 hour, with one health worker and one nurse to assist me). People started to gather around, curious to know what was happening and how events would pan out. I had heard stories of attacks on doctors. I knew about the mob mentality. I was frightened! What was better, fight or flight? How do I approach the situation?

But what happened next changed my perspective forever. Read on.

The safety of doctors has been an issue since time immemorial. Earliest studies of violence against doctors from the USA date back to the 1980s. 57% of emergency care workers in the USA have been threatened with a weapon, whereas in the UK, 52% of doctors reported some kind of violence.[2] In India, according to the IMA, at least 75% of doctors have reported as being exposed to assault (verbal, physical and psychological) [3] during duty hours. The incident that recently happened in Kolkata was a (yet another) wake up call in this direction. In India, where the allopathic doctor-patient ratio is low (1:11082) and not many doctors want to practice in the government or rural sector, doctors could be considered as a rare commodity and every effort should be made to protect them! [4]

WHY DOES VIOLENCE AGAINST DOCTORS MANIFEST?

So let us see what exactly happens. When a patient is no more, it is very natural that the patient’s relatives would grieve and try to console and counsel each other and form a support system. Some of the patient’s close relatives also look outward for support and to make sense of the profound loss. A popular theory about stages of grief according to the Kubler- Ross model are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Another popular theory (see pic) shows two possible outcomes of grief or a life-changing event – shock and denial or anger and bargaining. [4]

So when necessary support is not received by the patient in the first three stages phases, it leads to a crisis in grief management which can then lead to a violent outburst by the patients or their relatives. Also, there are several other factors leading to frustration which in turn cause violence. Few are listed here and may include:

Patient frustration factors

-

- Long queues and wait times

- No proper sitting, toilet or canteen facilities

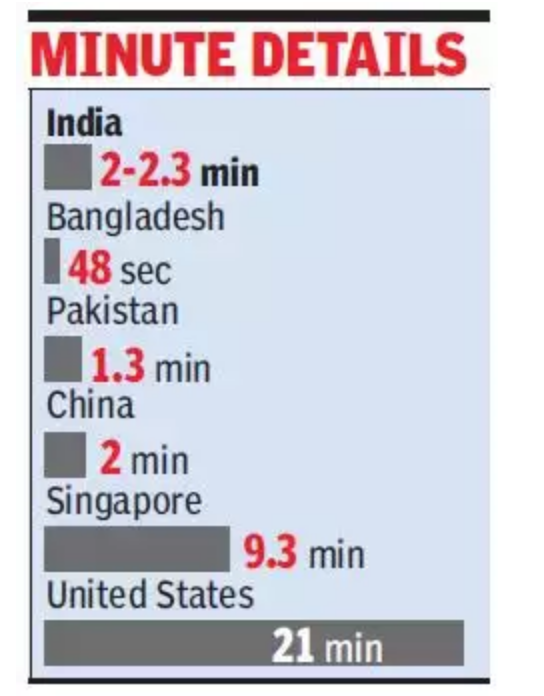

- After hours of waiting to meet the doctor, only 2 minutes or less time with the doctor

- Inability to understand the doctor’s notes or their own condition

- Expensive tests or medications prescribed by doctors they consider to be ‘money minded’.

- Out of pocket expenditures forcing people to empty their savings or utilize money kept aside for a better life.

- No sympathy or empathy and a very mechanised ‘assembly line’ delivery of healthcare.

Doctor frustration factors

-

- Long working hours

- Poor resources and infrastructure

- Organizational pressures to accommodate more patients in a fixed amount of time

- Better job opportunities, facilities and incentives elsewhere (in urban areas and private setups)

- Patients doubting their ability and prescription and violent outbursts from relatives

Other causes include irrational behaviour and personal vengeance. Also politically or economically motivated violence against healthcare institutions and doctors is not uncommon. For instance, Yi Nao, which literally means healthcare disturbance, started in China and is now a worldwide phenomenon, where self-proclaimed ‘do-gooder’ gangs extort money from hospitals alleging malpractice and share the profits with the patients.

Coming back: I gathered courage and informed the people that I am doing the best with the resources and the infrastructure available and empathized with them for their patience, which was seconded by the community health worker. When the man refused to budge and stood towering before me, I politely informed everyone, the reasons why further consults are not possible due to the looming danger. What happened then surprised me! The health worker and the local people told me not to worry, got together and ushered the gentleman out. He was asked to seek healthcare for himself and his family elsewhere. They even involved the local bodies to keep the entire family away from me and the premises.

THE CURRENT SCENARIO

Several legislations, including state bills, both for and against the doctors and the patients, are already in place [6]. But even with stricter laws in the advanced countries, assault on doctors still happens. Also, in spite of several laws being present on the patient’s side, there is a perception that the doctors are well connected and often get away unscathed. Also, certain media sources present sensational stories where gangs have beaten doctors and have got away with it. All these instances embolden the people to take the law in ones own hands.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

As patients

Doctors enter the profession with a spirit of helping others and always use their best judgement in the interest of the patient. Also, a doctor is just another human being, constrained by his knowledge and experience, trying his best not to make any mistakes, as in this field there are no second chances. Also, you may be dealing with a doctor who is as frustrated and helpless as you (reasons described above). Thus, ideally, in times of distress, one should approach and handle the situation in a calm and dignified manner and take help from higher authorities if things don’t turn out as per expectations or if you suspect any foul play.

As healthcare providers

Doctors should understand that the patient is a stressed person with heightened emotions and is probably worried about the personal, professional and financial toll this ‘mysterious’ disease would bring. Doctors should involve the patient in their diagnosis and treatment process i.e. shared decision making and given the times, take due consent and properly document the case irrespective of severity. Empathy is currently not taught as a subject at med school, and being so important in our daily practice, we should cultivate it along the way.

As healthcare organizations

Healthcare organizations have a statutory responsibility to commit to the safety of patients and healthcare providers, and ensure that their premises are safe and free from looming danger. Periodically reviewing safety protocols, quicker response by authorities, training security personnel and senior officials in managing escalations, using counsellors and better community engagement to build trust, are few of the instances that the institutions can undertake to manage and reduce harm during a crisis.

As policy-makers

Stricter enforceable laws could be implemented. For example, one thinks over a few times before assaulting a police officer as it is against the law to lay hands while he’s ‘on duty’. An extreme example is lifetime punishment, recently given to a South-Mumbai businessman for a hijacking prank on a popular airline. Such laws and its enforcement may deter people from even thinking of hurting doctors as the consequences of their actions are severe.

However, none of these solutions is sufficient by itself, but by working together we can all play our part in improving the safety of physicians.

CONCLUSION

Violence in any form towards anyone is deplorable, as is inciting one towards it. Doctors, patients and policy makers should be aware of the problems faced and initiate a course correction in a dignified and respectful manner. Additionally, such situations highlight the importance of having a trusted community health worker (CHW) by ones side (i.e. as a doctors’ or peoples’ advocate) and it goes a long way in calming down such people or events, as they are at a better advantage since they belong to the same community and the people place their trust and full faith in them to work diligently and have their communities’ best interests at heart.

A happy ending: A few weeks later, I saw a young boy arguing with some of my patients and his toddler brother crying outside my clinic. The health worker informed me that they were the children of the angry man, and the father refused to take them to a physician as he had to go to work, and they were asked to go away. The elder brother had enough of his little brother’s sickness and had tried to sneak him in. He pleaded with me for help. I couldn’t punish the children for their father’s mistakes, I was no judge here, I was just a doctor!

After cajoling the crowd, I managed to let the toddler in, consult and send a note back with a neighbor. I sent the small boy home with a local sweet and a smile on his face that was sweeter

References

-

http://www.jfmpc.com/article.asp?issn=2249-4863;year=2018;volume=7;issue=5;spage=841;epage=844;aulast=Kumar

-

Goodman RA, Jenkins EL, Mercy JA. Workplace-related homicide among health care workers in the United States, 1980 through 1990. JAMA 1994;272:1686-8.

-

Nagpal N. Incidents of violence against doctors in India: Can these be prevented?. Natl Med J India 2017;30:97-100

-

Human Resources in Health Sector. National Health Profile 2018. New Delhi:Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Directorate General Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2018:219